A Letter from Miami

Art Basel’s circus-like rotation of exhibitions, parties and launches still offers sparks of creative insight

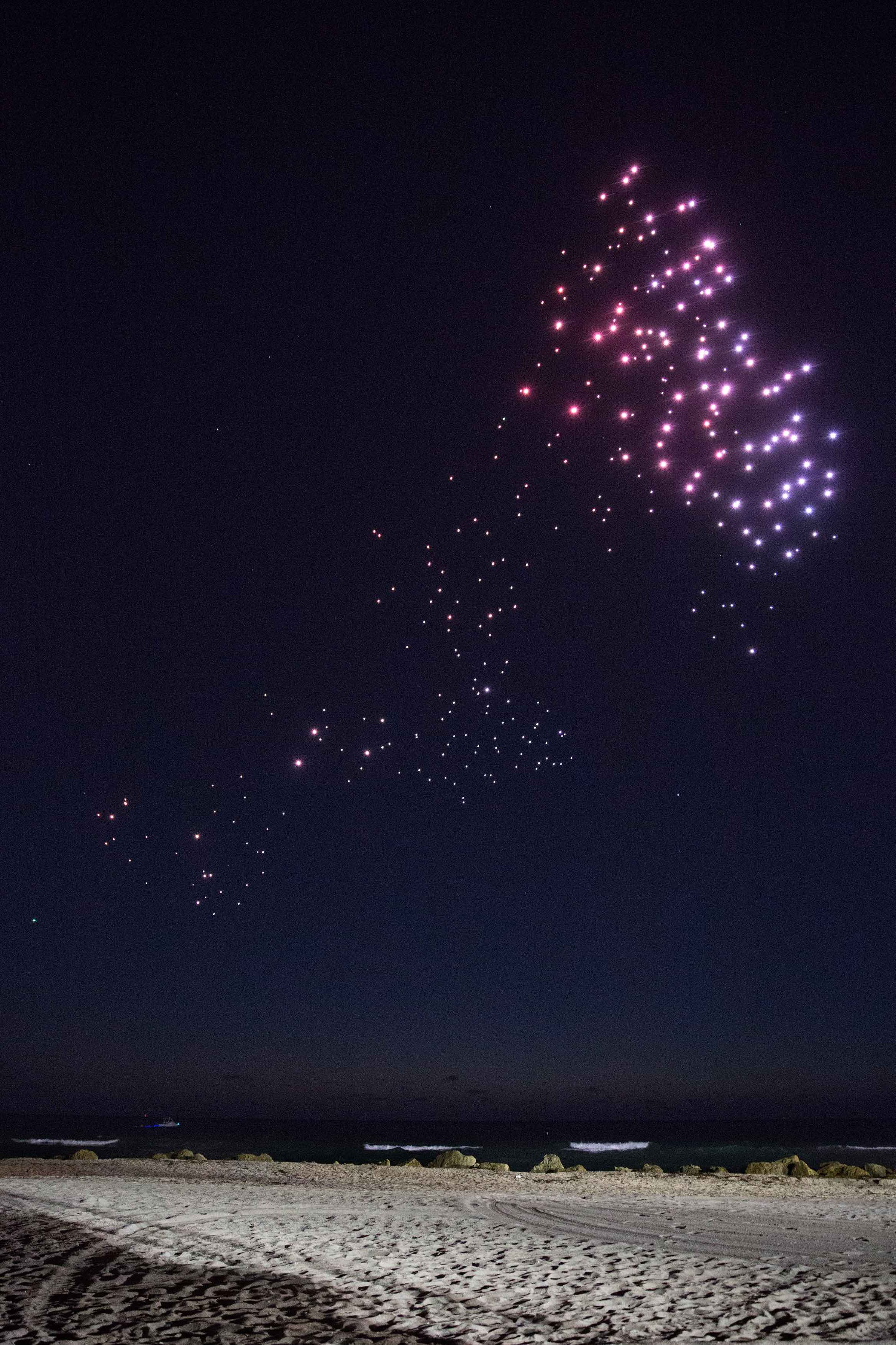

On the opening night of Miami Art Week, a flock of 300 illuminated drones flew in formation over the beach, soaring, dipping and turning in glittering, amorphous contours. The flying sculpture, named Freedom Franchise, was designed by Amsterdam’s Studio Drift and choreographed using an algorithm that mimics starlings in flight.

The technology was inspired by research into the flocking behavior of birds and principles of self-organization, and, by staging the performance, the studio aimed to highlight the delicate balance between the group and the individual. “The sacrifice made by the individual subjecting to the group gives off the illusion of freedom, creating a never-ending cycle,” studio co-founder Ms. Lonneke Gordijn said.

Unlike so many art-as-tech experiences, the performance had the crowd mesmerized. For five minutes all eyes were turned up toward the sky, and then, the whimsical constellation, presented in partnership with Future/Pace gallery and BMW swooped back down to shore.

Freedom Franchise, a kinetic sculpture comprising illuminated drones

Each year during Art Basel, Miami hums with electricity. The contemporary art fair, now in its 16th year, welcomes thousands of enthusiasts and collectors into its air-conditioned corridors, and this year over 250 participating galleries showed the usual mix of blue-chip trophies, emerging talents, Instagram bait, and genuine discoveries.

But Art Basel has come to involve much more than what is housed in the sprawling convention center. Miami now hosts over 20 satellite fairs including Nada, Scope, Pulse, Context and Untitled. At Design Miami, galleries trade in high-end design and collectable furniture and around town a see-and-be-seen crowd attends a circus-like rotation of champagne-fuelled launches, receptions, parties and performances.

This year’s most notable launches were new museums. The Bass Museum of Art (now just The Bass) reopened in Miami Beach following a US $12 million expansion courtesy of architects Mr. David Gauld and Mr. Arata Isozaki. Inside, Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone stole the show with a walk-in installation “good evening beautiful blue” consisting of 45 full-size mannequins of clowns. By turns macabre and humorous – and likely terrifying for coulrophobics – the figures appear seated on the gallery floor or slumped against the wall bearing expressions of boredom and fatigue.

"Good Evening Beautiful Blue” by Ugo Rondinone at the newly renovated Bass. Photo by Zachary Balber

Across the Bay the new Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) also celebrated its long awaited opening. The 37,000 sq ft cube-shaped building, designed by Madrid-based architecture firm Aranguren + Gallegos Arquitectos, has a façade covered in geometric panels and glows softly at night. The inaugural show: ‘The Everywhere Studio,’ features an exhaustive catalogue of recent art and economic history that examines how artists’ workspaces have shaped their production.

Some have questioned whether Miami can support yet another space dedicated to contemporary art, but the ICA aims to set itself apart by the accessibility of free admission and a trendy, central location in the Design District.

The newly opened Institute of Contemporary Arts Miami

Miami’s Design District continues to be a remarkable study in placemaking. Over the past decade architects like Mr. Sou Fujimoto, Mr. Buckminster Fuller and Ms. Zaha Hadid have contribute to the transformation of the neighborhood from an industrial zone into a creative retail destination complete with galleries, luxury boutiques, restaurants and showrooms and installations.

This year a fresh round of storefronts and installations were revealed, including a sculptural fountain by Urs Ficher at the newly opened Paradise Plaza, and Cloud Corridor , a pergola by French designer duo Mr. Ronan and Mr. Erwan Bouroulecc. Located along a pedestrian promenade, the structure is composed of steel and glasscolored ‘clouds’ that filter the sun and cast graphic shadows on the surrounding buildings, a perfect place to perch after visiting the area’s surfeit of fashion retailers.

Fashion seems to have an ever-larger presence at Art Basel as brands seek new ways to access a ready-made audience. This year the minimalist London-based label Cos commissioned British outfit Studio Swine (‘Super Wide Interdisciplinary New Explorers,’ run by Mr. Alexander Groves and Ms. Azusa Murakami) to create an updated version of New Spring, an installation that debuted to great acclaim at Salone del Mobile in Milan. Shown at a satellite proxy of Design Miami, the work is composed of a willow-tree-like structure that emits a continuous stream of vapor-filled elasticized bubbles.

While children under five (and by extension their parents), appeared to delight in the drifting grey bulbs, the allure was lost on me, save for the lingering image of a hundred bubbles bursting. The art world -- and Miami for that matter -- is its own particular kind of bubble, and a fun one to inhabit as long as the party goes on.

New Spring, an installation by Studio Swine for COS

Fashion houses aren’t he only ones capitalizing on the art fest. Property developers have also been savvy about using the fair to showcase their opulent homes by sponsoring events or partnering with organizations to connect their condominiums and mansions to the art world and catch the eyes of wealthy collectors. Often events are held at the listings themselves. “You have to realize that there’s something very important that real estate offers art collectors and that’s walls,” says New York-based art consultant Ms. Emily Santangelo.

But while many in the city coast along on a mutually advantageous wave of commerce, fashion and hedonism, there were also flashes of genuine artistic insight. At a polished mansion on Indian Creek (currently listed with Sotheby’s for US $24.5 million), the Chilean born, New York-based artist Mr. Sebastian Errazuriz sat before a jet-set crowd and talked about the role of the artist in a world poised for unprecedented technological and environmental disruption, (the latter being particularly critical for Miami, a low-lying coastal city that is vulnerable to storm surges and rising water levels).

“Up to now there’s always been this phrase going around that art doesn’t need to have a function,” Mr. Errazuriz said. “And I believe that phrase is wrong. We happen to be born at a time when life is about to change like it never has before and artists can’t be making work that’s just for themselves, about their own personal neuroticism, their ego, their childhood dilemmas.”

Mr. Errazuriz, who is known for mixing art and design in playful and provocative pieces that flirt with mortality (his early Boat Coffin sculpture, for example, has a functional motor and a plug on its side so the user can let the water sink the boat once he or she is ready to go) aims to startle the viewer and “steal a few seconds of awareness” to redirect their attention to what matters.

“I can’t be making paintings that look like Louis Vuitton bags,” he continued. “There are bigger issues right now. There needs to be a new generation of artists, designers and architects working with curators, critics, collectors and patrons but also with tech companies to incorporate a little bit of that emotional responsibility of everything that’s going to happen.”

New York's Perrotin Gallery at Art Basel Miami Beach

At Design Miami, the jury of this year’s Panerai Design award appeared to share his sentiment. Rather than a bestowing the Panerai Design Miami/ Visionary Award to a dazzling piece of industrial design, the prize was awarded to the Mwabwindo School, a collaborative project that brought together artists, designers, and architects who worked pro-bono to build a school in an underserved region of southern Zambia.

The project architect, Ms. Annabelle Selldorf, spoke about the need for a shift in consciousness around our environment and cultural heritage, and the advances made possible through meaningful collaboration. “This project is so much bigger than us as individuals,” she said. “And it has made a big difference not just for the school being built, but in how we have all learned to communicate with one another.”

If we can make drones that mimic the flocking patterns of birds—a complex continuum wherein each part responds and cooperates for the sake of the whole—surely the same principles can be applied in our collective response to global change.

This story appeared in the January 2018 issue of Portfolio magazine